Behavioral economics and customer experience – Part 1

Behavioral economics is a relatively new field. It combines economic and psychological theory and reaches new conclusions. Economic theory holds that people always behave rationally, optimizing their financial and other outcomes in a totally predictable way. (I have always found this theory odd, even when I studied economics. It was never clear to me that the stock market behaves rationally since half the people “rationally” believe they should buy what the other half are rationally selling. One half must be wrong, or at least sub-optimal.) Psychologists don’t care much for the economists’ view of the world, often proving that people behave irrationally. Behavioral economics combines the two world views, giving us new insights about the way people, including your customers, actually behave.

Key authors

The best-selling behavioral economics books are probably Predictably Irrational, by Dan Ariely, Thinking, Fast and Slow

by Daniel Kahneman, and Nudge

by Thaler and Sunstein. Ariely has written follow-on books that I found less innovative. Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economics, mainly for his work on Prospect Theory, which is covered in the book.

System 1 and System 2

Kahneman’s most relevant work concerns two different ways our brains function as we think: fast and slow. System 1 is the fast way and can be thought of as intuitive, jumping to conclusions on limited data. System 2 is the slow way, and requires rational thought. He and his colleagues performed numerous persuasive experiments that show that the rational System 2 is lazy, and prefers to do no work at all, especially when System 1 has already jumped to its own conclusion. I feel the existence of these two ways of thinking also explains most of what Ariely, Thaler and Sunstein have written. You may be familiar with a particular mathematical question that illustrates the difference between the two systems perfectly. It is called the bat and ball problem. Try to think quickly and answer it within two seconds.

- A bat and a ball cost $1.10.

- The bat costs one dollar more than the ball.

- How much does the ball cost?

Well? No matter what your final conclusion, a number almost certainly popped into your mind right away. Ten cents. Right? That answer is of course wrong. If that ball cost ten cents, and the bat one dollar more, the total cost would be $1.20. Appallingly, in large and repeated tests, over half the students tested at Harvard, MIT and Princeton got this wrong. System 1 jumped to the wrong conclusion while System 2 had a nice nap.

Relevance to customer experience

Customer experience publications and websites are full of System 1 content. By this I mean seemingly rational but wrong conclusions about cause and effect. My blog post on the importance (or not) of employee happiness and engagement for customer experience is a great example. Most practitioners believe it is among the very top factors impacting customer experience in most businesses. It is not. We just jump to that conclusion because it seems so rational that we don’t require any proof. What follows below is one example of a behavioral economics experimental result that I found particularly relevant to customer experience. I will provide more examples in the second part of this series.

The Peak-end rule

What customers experience and what they remember are different. For our purposes, the most relevant cause of the difference is what happens at the end of any interaction the customer has with your company. Let’s consider an experiment that Daniel Kahneman and his colleagues designed and called the “cold hand situation”. Participants were asked to hold their hand up to the wrist in what was perceived as painfully cold water. The actual temperature was 14 degrees Celsius, 57 Fahrenheit. (If you don’t think this is cold, get a thermometer and try it for yourself. I just did. Ouch!) The subjects were told they would have three trials, but actually only had two, in random sequence. In one trial, they put one hand in the water for 60 seconds and took it out. The other trial lasted 90 seconds and used the other hand. The first 60 seconds were identical. During the last 30 seconds, warmer water was added, taking the temperature up by one degree. The subjects were not given any information about what was happening.

The third trial

Participants were then told that they had a choice between repeating either of the first two trials. 80 percent chose the 90-second version. This is totally irrational, as the first 60 seconds are identical in the two situations. 80 percent chose to have extra pain. This is not because they were all masochists. They were predictably irrational. What they experienced and what they remembered were different. In the cold hand situation, the slightly-better last 30 seconds had huge weight, and carried the day.

So therefore…

From a customer experience perspective, this means that customers will most remember whatever happens at the end of any interaction with your company, no matter how painful or lengthy the overall experience. Let’s suppose you sell a technical product and have just gone through a lengthy telephone diagnosis and resolution process with the customer. Let’s face it, the customer believes the product should not have had a problem, so their attitude to the whole situation is not great. Rather than just saying, “Whew! It’s running again. Thank you for your patience.”, make the call a bit longer. “Let’s have a quick look at what happened next to other customers who had the same issue. Ah yes, here is how to avoid it in the future. And I can see that a lot of customers who had this issue also had this other problem. Can we take a quick look at that to make sure it is all working well?” Yes, it makes the call longer, but the end of the call is far more pleasant than the rest. Go for it.

Next week, in part 2

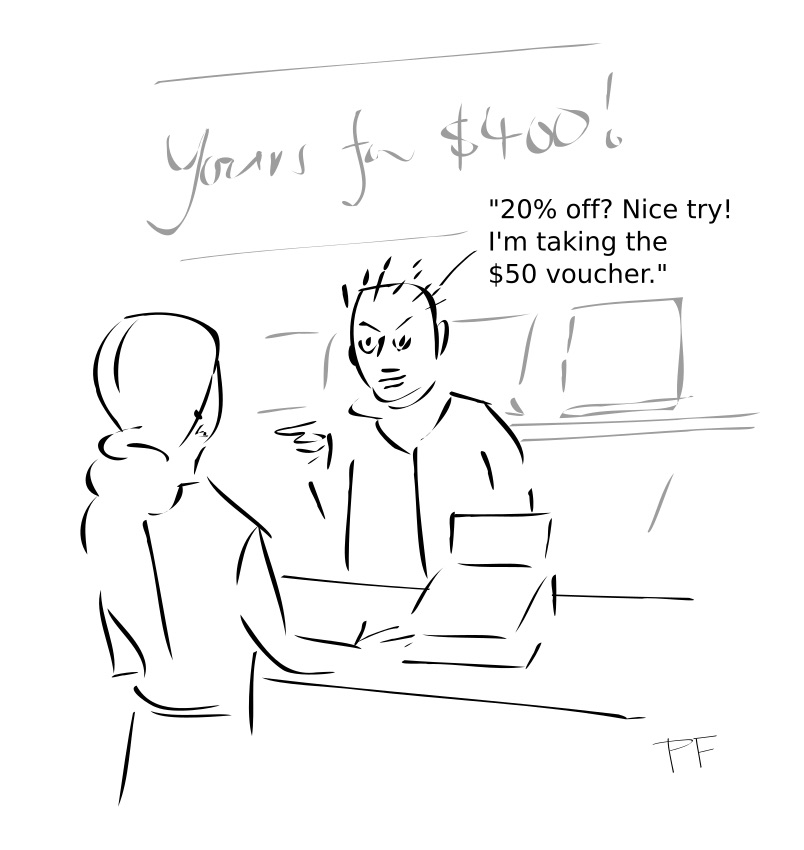

Next week I will write about the importance of price, and how to avoid customers taking revenge on your company. I feel the latter is quite topical, given the way consumers have used social media and other means to extract revenge on pharmaceutical companies perceived as guilty of price gouging. Remember, behavioral economics experiments often produce surprising results, and what you will read next week will be no exception.

Any comments you have are welcome below. As always, if you like what you are reading, please share it with your colleagues and friends and sign up for our weekly newsletter here. If you would like to send suggestions for future topics, you can email me at mfg@customerstrategy.net.

February 9, 2017 @ 5:48 pm

Great article, and a great reminder of the value of Behavioral Economics in our profession of CX> Thinking Fast and Slow – I need to read it again.