Tips for communicating the purpose of cost reduction (7-minute read)

I was talking to a former colleague yesterday. He described a recent meeting where he learned that major cost cutting still continues where we used to work. The discussion made me want to share what follows. I have seen cost cuts communicated well (which is rare) and poorly (which is the rule, rather than the exception). I hope the points below can help you to communicate the purpose and consequences of cost reductions more effectively. All but the smallest startup companies reduce costs, even those that have spectacular growth. Cost reductions are a necessary part of securing the cash you need to invest. Of course they are sometimes necessary for a company to survive too.

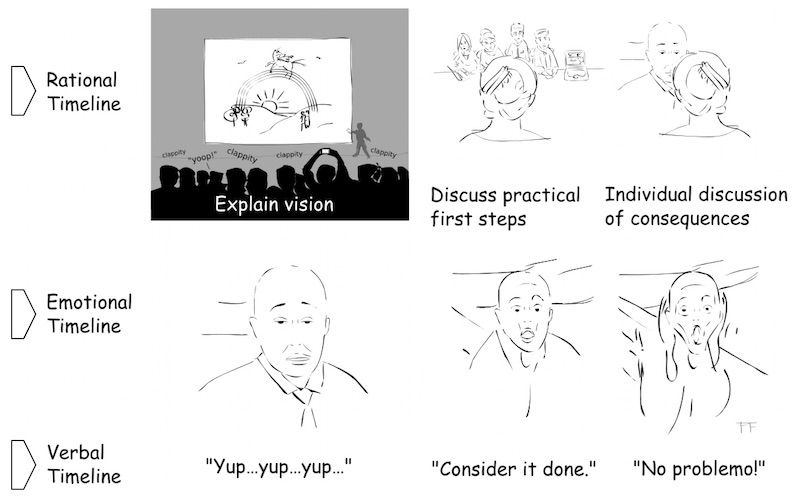

What I would like to accomplish here is to help you avoid major disconnects shown in the drawing at the top of the article. I believe the rational, emotional and verbal parts of your communication need to respect these guidelines to avoid project and company failure.

Most managers behave rationally. We believe that if we simply provide a clear and positive vision for the future and explain how cost reductions are on that path, everyone will understand. We set out the vision, and the practical steps required to get there. We then cover the positive and negative consequences individually. Seems rational. Unfortunately, the rational approach is not sufficient if human beings are involved. Our initial reactions to absolutely every new situation are intuitive, and based on emotion. It is a fundamental part of our human nature. It affects your employees and your customers too. What follows are some suggestions about why this happens and how to take it into account in your planning and execution.

Your customers believe they will lose out

As soon as your customers hear that you are going to cut costs and reduce people, they start to believe that they will be the losers. Your competitors will be quick to help this thought process along. It is absolutely critical that your formal external and internal communication covers the impact on customers, and not just as an afterthought. Customers need to be at the center of your message, assuming you are actually going to use the savings to invest in something for them. (If you are reducing cost just to survive, you must accept that some of your customers will jump ship.) News media will not help, as they will focus on the negative. There is some science around the way you need to communicate with your customers, and it is not at all intuitive.

If you only remember one thing

In the HP EMEA leadership team, all but one of the direct reports to the Managing Director were engineers. The one exception was our leader for Iberia (Spain and Portugal), Santiago Cortes, who graduated in mass media communications. The most important thing he taught the rest of us is “Communication is something that happens at the receiving end.” You must be able to put yourself inside the minds of the various types of people who will read what you write or listen to you. The difference between what you are trying to say and what they hear can be radical. At its most basic, avoid saying, or even thinking “I communicated it all to you. Didn’t you read my email?”

A lesson from Mark Hurd

Mark was and still is one of the world’s greatest experts in cost reduction. I was present when he once explained the principal difficulty he faced to the HP EMEA leadership team. (Mark is now CEO of Oracle.)

“When I started to talk about where we would get the money to invest in doubling the size of the sales force, I did my best to spend half my time talking about growth and the other half about cost. Whenever I would speak to a group of employees, I got into the habit of asking people around me what I had just spoken about. With the 50:50 time distribution, everyone told me I had only spoken about cost reduction. I found that I had to spend over 80% of the time on growth before the audiences would accept that I said anything at all about growth.”

A lesson for managers from a Nobel winner

In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Nobel-winner Daniel Kahneman covers loss aversion, part of his work on Prospect Theory. In short, humans care far more about what they could lose in any given situation than what they could gain. This is not at all what classical economic theory predicts. Classical economic theory is simply wrong; humans and Econs behave differently. Kahneman provides many examples of experiments. One of my favorites is about a potential new chemotherapy treatment for cancer. Half the oncologists were told “The first year survival rate is 90%” and close to 80% said they would prescribe the new medicine. The other half were told “The first year mortality rate is 10%.” In this group, only 50% of doctors were willing to use the treatment. The two proposals are identical, but one is phrased in terms of the potential loss.

If your company is obviously in financial difficulty, loss-aversion communication is relatively simple: “We need to save $85 million this year or we will not be in business next year.” If corporate results are fine, the message has to be more externally-focused, ideally on your competition. “Betacorp is out-investing us in sales, marketing and sales support. We need to find an additional $85 million to invest in sales or Betacorp will continue to steal our customers.” What this does is position the enemy as outside the company. The enemy always needs to be outside. If your leaders believe the enemy is inside the company, you will not survive.

Taking responsibility

Taking responsibility for your actions is the key to avoiding revenge, as Dan Ariely and other behavioral economists have discovered. Let’s use a parallel example to illustrate this point. When you ask sales people why they just won a big deal, they will almost always attribute the win to something in their control, such as the great relationship they have with the customer. When you ask them why they just lost a bid, they will attribute it primarily to something outside their direct control, such as price. When it comes to the ups and downs of corporate results, the same tendencies apply. CEOs attribute positive achievements to their creativity, great strategy and wonderful execution. When things go badly, they attribute it primarily to things outside their control, such as a financial crisis, or some change in the market that they say nobody could conceivably have anticipated.

Avoiding revenge

In his book The Upside of Irrationality, Ariely describes studies of litigation when doctors apologize to patients for errors they have made, rather than hiding from the truth. Where they apologize, they are far less likely to face malpractice suits. Where they simply say “I am sorry. I made a mistake. I understand how it happened and I have learned from it,” patients are more likely to forgive them, and give them another chance. In corporate life, employees can find all sorts of big and small ways of taking revenge for leadership errors. To avoid revenge, and to encourage general employee empathy for the situation in which the corporation finds itself, try apologizing. “On behalf of the leadership team, I want to apologize to all our employees, customers and partners for the unpleasant times we are now facing. My team and I made some poor strategic decisions, and let our competitors beat us in the market. We now need to find the money to invest in the following three growth initiatives, to recover our rightful place…” Try it. On top of being truthful, it would be so unusual that it would attract a lot of positive press.

What you have and what you don’t have

In my own words, cost reduction is about what you have, and growth is about what you don’t have, by definition. This means that loss aversion theory applies to cost reduction. Once you talk to the general population of your company about cost reduction, you are talking about potential loss and that will erase all memory of anything you may say about potential gains. In the Mark Hurd example, the customer-facing sales people felt safe, as they had been told their numbers would double. Everyone else felt paranoid, including the pre-sales and sales operations people. In short, nobody except the sales people heard the growth message at all. Most people felt they were walking around with a big target on their backs.

Problem: cost reduction comes before the investments

Communication is further compromised by the fact that you usually need to achieve cost reductions before you can make the additional investments they allow. This means that the only short-term communications and actions tend to be on cost. Again, people understand these discussions really well, because they are all about the people, buildings and supplier contracts they already have. The possible discussions about making growth happen are far more vague. The market and other factors can change too. In one HP case, cost savings were designed to allow an investment of over $100 million in automation of a labor-intensive business. It took so long to achieve the savings that other things had change and almost none of the automation investment was made as planned. Unfortunately, that in turn drove a need for further cost reductions, as competitors made the investments.

Accelerate communication to those who are going to lose out

To limit paralysis, it is critical to communicate as quickly as possible to groups who are going to lose out. Don’t spend much time with teams who can see they are going to gain. In the absence of communication, groups that might lose out will form their own mental images of a reality that is far worse than the worst situation you have in mind for them. Understand that everyone who has not explicitly been told they will gain will believe they lose out. Unfortunately, there are countries, mainly in Europe, where the communication processes are regulated and you will not be allowed to communicate the bad news quickly. You need to build this into your plan, and also to plan on having worse than average business results in those countries until communication is allowed.

Customers too

In the absence of clear positive messages from you, your customers will believe they are losers too. Your brand image will suffer. Local websites will skip any positive messages in your press release and lead with “Acme to cut 50 jobs in Smalltown. Community devastated.” Your CEO needs to speak to the leaders of your larger customers directly. Your website and general messaging needs to talk almost exclusively about where you are investing. Don’t forget to mention complexity reduction, especially if you are shutting down an entire business. The unfortunate source of the investment funding needs to be less than 10% of your content. Even at that level, it will still be the majority of what people at the receiving end remember. Ensure all of your sales people understand and can communicate the messages concisely. They will be at the front line when competitors spread fear, uncertainty and doubt to your customers.

Some behavioral economics tips for your communication

In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman provides some research-based tips for credible written communication. These are not at all intuitive:

- Take the following two statements:

- Mahatma Ghandi was born in 1865

- Mahatma Ghandi was born in 1868

The one in bold text is far more likely to be believed. Both statements are in fact false as Ghandi was born in 1869.

- If you use color, your message is more likely to be believed if you write in bright blue or red, rather than in medium shades of green, yellowor pale blue. (And I think you can tell that yellow is hard to see against a white background on a computer screen.)

- Kahneman’s colleague Danny Oppenheimer showed something counter-intuitive in his study titled ‘Consequences of Erudite Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity: Problems with using long words needlessly’. Surprisingly, using complex vocabulary where simpler words could be used turns out to be perceived as a sign of poor intelligence and low credibility. This is, of course on top of the more general consideration that you should write at about an 8th grade level when addressing a multinational audience.

- If you have to quote or reference someone else to make a point, make sure their name is easy to pronounce. References from people with difficult names are considered to be less credible. This is a tough message for many people.

- Finally, and more intuitively, if you want your most important short points to be remembered, make them rhyme. People will remember “Woes unite foes” far more easily than “Woes unite enemies.”

Reward systems are quite different for working on cost compared to growth

Now to cover communication to people driving the cost-reduction work. I spent many years working hard on cost reduction. I felt that I was being paid quite well, and was regularly promoted. I must say that I lived a sheltered existence. For the first years of my career, I worked in manufacturing, distribution and logistics locations where cost mattered a lot. They were also locations where I did not come into regular contact with people who worked on growth. Once I moved to Geneva, I found myself surrounded by them. I quickly discovered that people who bring growth are paid far more, and receive higher bonuses than those who work on cost.

I remember an annual salary review discussion with one of my managers. I had a formal cost reduction goal for a European program I was managing. My team had over-achieved by about 20%. I was given a perfectly average salary increase and a small bonus. I was disappointed and asked why. My boss told me “You were just doing your job.” This is all connected to the ‘What you have and what you don’t have’ discussion we have already covered. I was just doing my job. Anyone who brought in a small amount of growth was a genius, and received maximum rewards. This also matched the formal corporate goals of DEC. Growth was listed as the top priority. In Europe, we were a $5 billion company and had a formal plan to get to $10 billion. Cost reduction did not make the priority list.

If you are going to work on cost reduction…

So, if you are going to spend a lot of your career on cost reduction, be sure it is actually in the formal top priorities of your company. If it is not, it is really not worth the pain. If it is not a formal priority, you will be causing pain all around you, without the necessary support from the top. I suppose timing is everything. All companies go through tough times at some point. If you can lead through dark times with support from the top, celebrate the resulting financial performance by working on something more positive for a while.

As is usually the case, this is a slightly-edited version of a chapter in one of our books; in this case Customer-Centric Cost Reduction. All of our books are available in paperback and Kindle formats from Amazon stores worldwide.