Avoiding confirmation bias when interpreting CX, NPS, indeed any research results

Some thoughts on how to avoid confirmation bias when interpreting research results. While I will use Net Promoter System research as an example, this applies to all forms of customer and other research. And… I will suggest how you can use cognitive biases to your advantage when presenting your results or persuading people to invest in a project that is based on your results.

System 1 and System 2

In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow[1], Daniel Kahneman describes two ways our brains function. He refers to them as ‘System 1’ and ‘System 2’. At their most superficial, you can think of System 1 as intuition, and System 2 as rational thought. He offers persuasive arguments that System 1 acts first, and that System 2 is lazy, and does its best to avoid work.

Relevance to NPS and other customer experience research and improvement systems

For NPS to be a trusted metric, it must work for both System 1 and System 2. The Ultimate Question 2.0 by Reichheld and Markey is the reference book for the Net Promoter System. It concentrates on System 2. This book’s content on survey design, improving response rates and things like the automated analysis of verbatim responses all appeal to System 2. I consider the System 2 work to be necessary but insufficient for success. You also have to appeal to the fast-acting intuitive reactions of System 1 thinking. The following are some items for you to consider.

Sequence of presentation

Kahneman describes an experiment set up by Solomon Asch [2]: subjects were given descriptions of two people and asked for comments on their personalities. Here they are. What do you think of Alan and Ben?

● Alan: intelligent, industrious, impulsive, critical, stubborn, envious.

● Ben: envious, stubborn, critical, impulsive, industrious, intelligent.

Most people describe Alan far more positively than Ben. Because the first word used to describe Alan is ‘intelligent’, the more negative character traits are considered to be justified. However, the words used to describe Alan and Ben are identical. Only the sequence has changed. The first thing that is presented has a disproportionate effect on your message, and sets the tone for all the rest. For example, if the overall message you want to communicate is that your company is making good progress, don’t start with the only negative story. When you are going to talk about what you need to improve and what is going well, start with what is going well. Of course, if you have just taken over the customer experience responsibility, you may want to be Machiavellian and start with the bad news, implicitly blaming it on the prior leadership. You could then reverse the sequence for the same information a few weeks later, and people will think you are making progress. Naturally, if you do this blatantly or often, you will lose trust.

Jumping to conclusions

We all jump to conclusions without being aware of it. Kahneman offers the example, “Ann approached the bank” to illustrate this point. You almost certainly formed an image of a woman walking towards a bank, possibly to deposit money. However, the statement is ambiguous. If we had also been told that Ann was on a canoeing trip, our conclusion would be different and we would see her paddling to the side of the river.

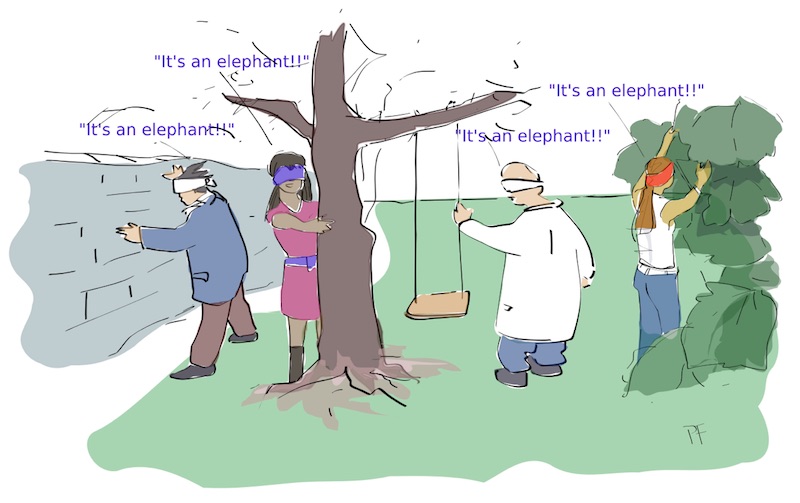

A lot of customer experience information is ambiguous. People’s System 1 will jump to conclusions and System 2 will sleep, unless you force it into action. You have probably heard of the metaphor of blind people trying to identify what they are touching, when each is able to feel just one part of an elephant. Turn this on its head and you have confirmation bias. If your audience has been primed to think, for example, that customer service is awful, they will use whatever they can in your data to support that conclusion, and may not even realize they are doing so.

How to get System 2 to work

In other words, how do you get people to react totally rationally to the NPS numbers you present and the financial business case you may be making? The sad truth is that you can’t do much about it. Your best solution is to force your System 1 to look at what you are going to present. Think in terms of someone who is going to ignore most of the data. What are they going to see when they look at your slides? What are they going to hear when you speak? Their intuitive, emotional reaction will win out. System 2 will act only for brief periods. Plan on it.

There is some science that suggests that asking people to do a simple mathematical puzzle that requires System 2 to get the correct answer will help engage System 2, at least for a brief period. Priming people by giving them a puzzle to do in a break, or just having it on the screen before your presentation may help. There is also evidence that making something difficult to read forces System 2 to engage. In any case, you should kick off by using a real customer quote or example, appealing to your audience’s emotions before you start showing data.

It’s all quite tricky. We have to learn to combine rational and emotional thinking to be effective communicators.

[1] Daniel Kahneman: Thinking, Fast and Slow, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011, ISBN 978-037427631

[2] The full set of Asch’s experiments in this area is described in the article below. The example used is “Experiment VI” in the article.

http://www.all-about-psychology.com/solomon-asch.html